Orang Laut in the National Collection and Narratives of Erasure

Written by Loh Pei Ying, published 12 August 2024

A forgotten people. A lost paradise. A bygone way of life.

That's how Singapore's Orang Laut are often described. As though the tides of time are unstoppable forces that washes away their history, memories, and heritage. But this absence from our histories, textbooks, and land is not by chance. Forgetting and remembering are conscious and selective activities.1

How may we account for this missingness?

Museums as memory repositories

All around the world, museums often represent what a country treasures most. They are institutions—warehouses—of memories, designed to collect, preserve, protect, and communicate what a community decides as valuable. 2

In Singapore, our museums under the National Heritage Board (NHB) have taken on the mantle of being the custodian of our national and collective memories, "responsible for telling the Singapore story [...] and imparting our Singapore spirit."3

A composition of nine different museums, the NHB has combined all 220,000 over artefacts into what it calls the National Collection.4 About half of this collection has been datafied to be put on digital display on a multimedia web repository and database called ‘Roots’.5

Collective memories are important to the formation of our identity as a people. They represent what we choose to remember and forget, narrating a past that forms a national articulation of who we are. Where do our Indigenous communities live in our collective memory?

Rooted in a colonial past

Singapore's museums have colonial beginnings, starting in 1823 with the Raffles Museum and Library. The collection was given a building of its own in 1887, which was refurbished into the National Museum of Singapore in 1960 for nation-building purposes.6 Singapore's museums today are built from an inheritance from the colonial collection. The Raffles Museum was heavily influenced by European sensibilities and museology. It collected materials concerning both natural and cultural heritage, taxonomising the material culture of regional communities.7

Museums are not benign institutions, and even more so their digital counterparts. They are often spoils of colonialism; evidence of the settler's exploits on foreign land. Collections of curiosities and trinkets they've amassed to display and study in the name of knowledge. They remove artefacts from their social fabrics, placing them in sterile rooms, far from their original environments.

Loss of context, loss of cultural meaning, destruction of a direct connection with life, promotion of an esthetically alienated mode of observation, instigation of a passive attitude toward the past and of a debilitating mood of nostalgia–the museum seemed embody all these ills of the modern age, an age that, by its own account, had forsaken the immanent ties with tradition that had blessed every previous era.8– Didier Maleuvre, Museum Memories

Museums are institutions of power. They transform organic, fluid, and spontaneous memories into still nuggets—frozen in time and space—in the name of knowledge. They shape us a people through collective remembrance and forgetting, and fuel stories of Singapore that form our identities.

Orang Laut in glaring omission

The colonial world is a world divided into compartments. [...] Yet, if we examine closely this system of compartments, we will at least be able to reveal the lines of force it implies.9― Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

Of the 109,757 artefacts displayed on Roots, the words 'Orang Laut' are only explicitly mentioned in the descriptions of 14 artefacts. A wider search of mentions of the names of their islands and spaces, such as Pulau Brani, Pulau Seking, or Pulau Belakang Mati, brought up another 205 artefacts. Majority of these are housed within the National Museum of Singapore's (NMS) Collection.

According to NMS, there are an additional 40 artefacts, largely of fishing paraphernalia, that are not displayed on Roots.10 These total to 249 artefacts. Of this vast repository of over two hundred thousand, only a tenth of a single percent has traces of Orang Laut. They are hardly present in Singapore's collective memory.

The vastness of their relative missingness is astounding, but this quantification only tells us one part of the story. The omission, while glaring, is insufficient to understand the mechanisms and layers of erasure.

These 249 artefacts are data that "is a thing, a process, and a relationship we make and put to use", and is "in need of interpretation".11 They reveal to us the stories we hold in collective memory of Singapore's Indigenous communities.

Orang Laut are "othered" through collection

The objects of research do not have a voice and do not contribute to research or science. [...] An object has no life force, no humanity, no spirit of its own, so therefore 'it' cannot make an active contribution.12– Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies

Collection is an "Othering" process. Indigenous researcher Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues that when people become the subject of research, they become objectified, voiceless, and without agency.

This process of rendering a people voiceless is most viscerally seen in the material type of these artefacts, where Orang Laut are framed and mediated only through documents. Of the artefacts that had their materials described, they were nearly all photographs or documentary materials taken during the 19th to 20th centuries. Most of these are ethnographic in nature or promotion materials of tourism. Majority do not depict people, and much less of Orang Laut.

When presented with the 40 fishing artefacts, Orang Laut descendants contested the way these were catalogued. One descendant from Pulau Semakau commented that these objects felt sterilised, with no stories or rituals attached to them. Many of these materials had more than functional purposes. For example, bubu traps, a type of fish trap unique to Singapore's southern islands, can only be made when the moon is fuller to ensure the traps are imbued with greater power for a more bountiful catch.13 These artefacts and the way they are recorded in the museum do not acknowledge the knowledge systems they originate from.

For Orang Laut, objects are more than just material things. They are imbued with supernatural powers and profound spiritual, social meanings. The simplest objects can be their most prized possessions and are regarded as heirlooms.14 Yet when collected into a museum, they are rendered lifeless. Their Indigenous practices and knowledge resists essentialism. These objects have shifting names and meanings, depending on the context they are used in. For example, a Serampong (spear) changes in name depending on which island they were from, and sometimes it can be mata tiga (three eye), but can also be counted up to four or five. Some of these objects were also mislabelled, like the mata pancing and tunda, parts of a fishing line, being catalogued as a candat.15

Fuelling colonial master plots

The settler makes history and is conscious of making it. And because he constantly refers to the history of his mother country, he clearly indicates that he himself is the extension of that mother-country. Thus the history which he writes is not the history of the country which he plunders but the history of his own nation in regard to all that she skims off, all that she violates and starves.16― Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

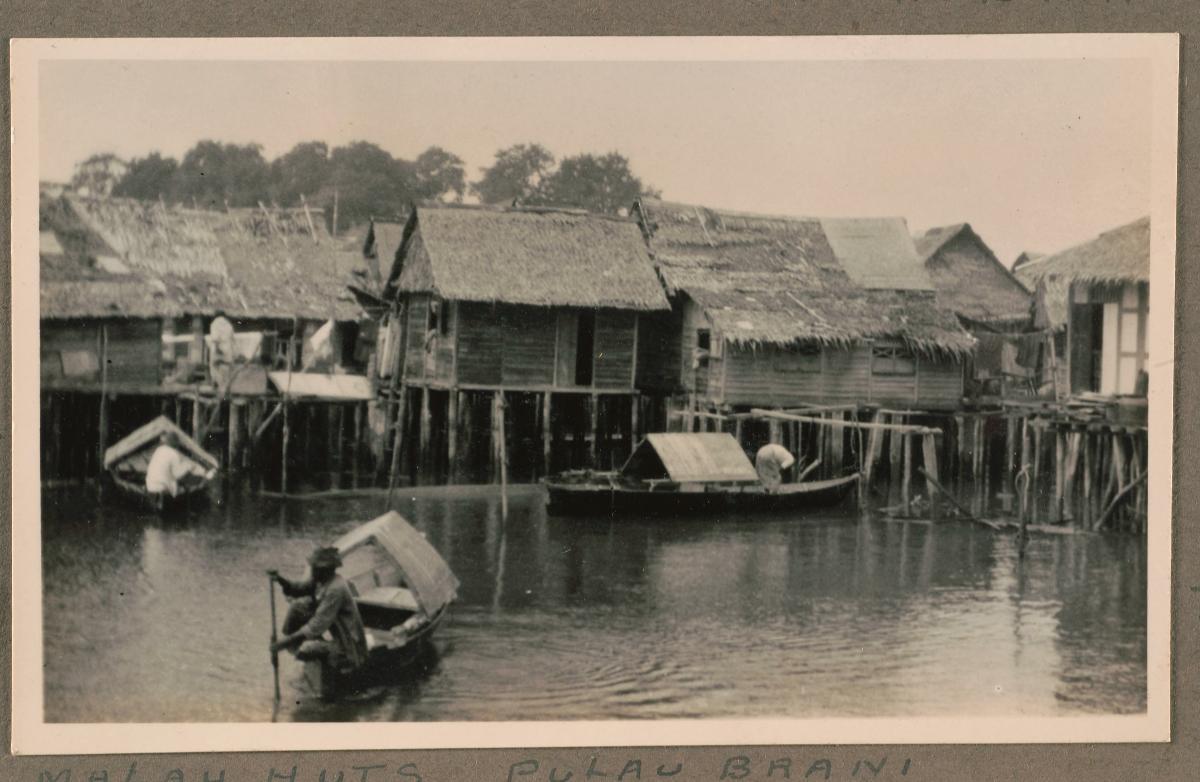

The selective collection of materials related to Orang Laut fuel colonial narratives that justify erasure. The fixation on only photographic documentation evidences a terra nullius narrative: that these were lands and seas without people, and history begins with British settlement. More specifically, several of these images encourage the colonial-inherited state-driven narrative that Singapore was merely a "sleepy fishing village" prior to British colonisation.17 For example, one photograph of Orang Laut homes describe them as a "fishing village", painting a sedentary and backward perspective of these communities.

Fishing village, Pulau Brani, 1920s, Singapore, Gelatin silver prints, Collection of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board 2008-00415-053

Beyond paper materials, the only material culture in the National Collection concerning Orang Laut are of fishing paraphernalia. This cements the narrative of Orang Laut as a primitive people, known only for their fishing skills.18 It encourages a long and strongly held opinion of them as a "low civilisational" and "subsistence" community.19 They are recorded in national memory as a community without art or culture, even though there is a wealth of knowledge to be learnt from them.

To make matters worse, these fishing paraphernalia are not displayed on Roots. These objects also do not have any accompanying descriptions for reasons unknown. According to the museum, it is likely due to the "incompleteness of the artefact records on the [National Heritage Board]'s internal database" where blank fields, or lack of data cleaning, prevents these items from being uploaded to Roots as they do not meet the standards for "Online Display".20

There is so much more that the Orang Laut has to offer to Singapore's history. Artefacts that would be more representative of their past could include a kerosene lamp used for fishing at night, or the beautifully and skillfully crafted boats Orang Laut were known for, or details on their herbs and natural remedies.21 These narratives and exclusion of their heritage and experiences in national memory causes frustration, annoyance, and anger.

The histories of Orang Laut and their lands are also rewritten through these short descriptors that accompany artefacts. These blurbs of barely a hundred words focus largely on Singapore's colonial, military, and economic history. An data analysis of these descriptors show that besides "island" and "Singapore" which are the top two most frequently occurring words, "sentosa", "development", "opened", "built", "tourism", "british", and "military" are amongst the top twenty most frequently used terms.

A large number of the photographs are about Pulau Blakang Mati, but they describe little of its pre-colonial past. Instead, the island has been renamed to Sentosa and is now a popular holiday destination, and prior to that was repurposed by the British into a military base. The histories of these islands are rewritten as ones that begin with its colonial uses, such as Pulau Brani being a repair dock for ships and a naval base, Pulau Bukom as an oil depot, and so on. These vignettes focus on Singapore's economic might and military purpose, with little to no acknowledgment that Orang Laut have resided here for centuries.22

On the rare exception that Orang Laut are mentioned, they are described as "claiming to be the original inhabitants", "descendants of pirates", and having "abandoning their pet cats on the island" which caused concern from animal welfare groups. While these may not necessarily be untrue, the narrative is heavy with negative connotations and undermines their legitimacy to these spaces. There is no mention of their contributions to Singapore's history, or the finer attributes of their way of life.

Whose stories get told in multicultural Singapore

Multiculturalism tends to erase real and historical inequality by treating different cultural groups as equal. For Indigenous peoples, this form of equality undermines legitimate claims and grievances against the colonial state.–Jenny Bol Jun Lee, Jade taniwha

According to historian Michael. D. Barr, the Singapore state has claimed a narrative that the island's pre-colonial past is "unknowable", and "irretrievably lost in the mists of time" despite evidence that says otherwise.23 We see this perspective perpetuated in media reports of Orang Laut that describe their heritage as "forgotten",24 "disappearing",25 or "lost".26 Academic studies also reflect this perspective, and describe the Orang Laut's disappearance from our histories and landscapes with a sense of inevitability, using words such as "decline" and "final".27 This narrative does not account for the active erasure and structural violence committed on Orang Laut communities.

When queried on its strategy to collect artefacts related to Orang Laut, the museum answered that it would, but only "if they are deemed to be relevant and significant for illuminating Singapore's social history. The provenance of these objects should also be clear, and preferably in good condition".28 Whether these choices are conscious or intentional, one may surmise that the Orang Laut's significant omission from the National Collection suggest that much of their material culture does not pass the threshold required. Perhaps, because of the belief that Orang Laut artefacts may be 'lost' to time or less likely to endure conservation.

This erasure is most evident when we look comparatively to the Peranakans, a mixed-heritage community of settlers intermarrying with locals in Southeast Asia. These were largely Chinese, Indian, Arab, and European settlers known to have adopted local language, customs, and material culture.29 In 2008, the National Heritage Board set up the Peranakan Museum, to reflect "the nature of Singapore's history in the world as a port city composed of many different communities who have lived and worked together".30 It now houses over 5200 artefacts, spanning a wide range of material culture from such as ceramics, furniture, and fashion. They demonstrate that collecting is more about the will to catalogue, and less about the material condition of artefacts.

The Peranakan Museum's raison d'etre is to exemplify the best of Singapore as a port city and confluence of cultures. But the Orang Laut are not less important to Singapore's history flourishing entrepot for trade. In fact, they were integral in facilitating trade for centuries. There is rich evidence that they were some of the best seafarers in maritime Southeast Asia, and commanded the Straits of Melaka for centuries, significantly shaping Malayan history.31 The crucial difference between the two groups is that Peranakans are an exemplary community of settlers who thrived under the colonial administration. The Orang Laut on the other hand, have been constantly described as dirty, unkempt, and backward.32

Peranakans are an interesting comparative point for the Orang Laut, as they are symptomatic of how indigenous histories have been rewritten, or in this case, appropriated. Many elements of Peranakan material culture are seen to be characteristically Indo-Malay, yet are overwhelmingly only represented in the National Collection in association with Peranakans. For example, the sarong kebaya, a tunic and long cloth attire typically worn by women across Southeast Asia, is mostly catalogued only in the Peranakan Museum.

Erasure

It is a devastating question answered by the structural racism that Malays and other ethnic minorities in Singapore battle with in a Chinese-dominated society. The 'dangerous native' trope, though shape-shifting over time, is one sticky strand of colonial racism. Ask a Singaporean for an understanding of Indigeneity and they are more likely to associate it with ethnonationalist politics (their cues coming from the politics of neighbouring Malaysia).33– Nabilah Husna Binte Abdul Rahman, "Tending to wounds"

The National Collection are material manifestations of our collective memories that shape our histories, narratives, and identities. The Orang Laut have lived on this land and sea for hundreds of years, and their omission from our coffers of memories is stark.

This missingness is not incidental. They are not forgotten but erased, intentionally left on the margins, and used only to serve the Singapore story: an island nation born of the entrepreneurial spirit of settlers who found a blank canvas of economic opportunity.

The Singapore story has always been rooted in racial anxieties; we are a fragile nation, held precariously together by tolerance and superficial appreciation.34 Its insistence on multiracialism and cultural difference encourages separability,35, and introduces an essentialism that erases the colour and nuances that make us unique.

This erasure doesn't manifest simply in narrative form. It evidences and justifies erasure materially, and Singapore's Orang Laut are still facing its reverberating consequences. None of the islands they hailed from today are accessible to them. They are home, but also not. They live in constant threat of disappearance, where they have to continually insist on their existence.

It is Singapore's loss. There's wisdom, reciprocity, adaptability, abundance and knowledge to be gained with the holistic inclusion of Orang Laut and Indigeneity in our national memories and narratives. But the answer is not in collecting more materials in institutionalised forms, but how may we imagine a repository of memories of a significantly different nature?

Methodology

About the data

Data used for this analysis can be accessed

here. To gather the data for analysis, I scraped Roots (" https://www.roots.gov.sg/) using Selenium, a powerful python library that allows automation and scraping tasks on

Javascript-heavy websites. I used specific unique terms due to the sensitivities of Roots's

search engine. For example, searching for "Orang Laut" also presented artefacts that mention

"Orange". To avoid flooding the data with unrelated objects, I narrowed down my search these

specific terms: Laut, Selat, Seking, Brani, Belakang Mati, Bukom, Bendera, Bukom, Sebarok,

Semakau, Senang, and Sudong. In making a separate dataset about Kebaya, I repeated the same

process for the term "Kebaya".

This dataset was merged in Python and manually cleaned. Artefacts with the above terms but unrelated to the island or Orang Laut were removed. The year_period of the dataset was manually categorised into larger time periods for analysis, i.e. Late 1980s was sorted as 20th century (late). Other calculations were made using Google Sheet's Pivot Tables and exported into Flourish.

For the word frequency analysis, the total corpus of text from the descriptors of these artefacts were put into Voyant Tools, a web-based text analysis and visualization tool designed for digital humanities and text mining.

About interviews

Part of this research was informed by a Focus Group Discussion with five Orang Laut descendants

on July 19, 2024. Their inputs informed parts of the analysis in this critique. I also drew on

an email correspondence with a curator at the National Museum of Singapore on July 20, 2024.

About non-english words

I have made the decision not to italicise non-English words as is traditionally practised. Read

Jumoke Verissimo's

"On the Politics of Italics" to

understand why.

About images

The images published here are Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage

Board.

References

- 1 Siegfried Schmidt J., "Memory and Remembrance: A Constructivist Approach," in Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, ed. Astrid Erll, Ansgar Nünning, and Sara Young (Berlin/Boston, GERMANY: De Gruyter, Inc., 2008), 197, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ed/detail.action?docID=364668.

- 2 "Museum Times," in Museum Memories, by Didier Maleuvre (Stanford University Press, 1999), 9, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503617155-004.

- 3 National Heritage Board, "About NHB," accessed August 8, 2024, https://www.nhb.gov.sg/who-we-are/about-us.

- 4 Sean Lee, "Digitisation of the National Collection: Challenges and Opportunities" (The Digital in Cultural Spaces, Singapore: Culture Academy Singapore, 2016), 67, https://www.mccy.gov.sg/-/media/Mccy-Ca/Feature/Resources/Conference-Papers/The-Digital-In-Cultural-Spaces-Publication/The-Digital-In-Cultural-Spaces-Publication.pdf.

- 5 National Heritage Board, "Roots," 2024, https://www.roots.gov.sg/.

- 6 Su Fern Hoe and Terence Chong, "Nurturing the Cultural Desert: The Role of Museums in Singapore," The State and the Arts in Singapore: Policies and Institutions, March 1, 2018, 4, https://doi.org/10.1142/9789813236899_0012.

- 7 Hoe and Chong, 4.

- 8 "Introduction," in Museum Memories, by Didier Maleuvre (Stanford University Press, 1999), 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503617155-003.

- 9 Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington, Reprinted, Penguin Classics (London New York: Penguin Books, 2001), 29.

- 10 According to email correspondence with the National Museum, Jul 20, 2024.

- 11 Marika Cifor et al., "Feminist Data Manifest-No," Feminist Data Manifest-No, 2019, https://www.manifestno.com..

- 12 Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Third edition (London New York Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022), 70.

- 13 Firdaus Sani, Focus Group Discussion, Jul 19, 2024.

- 14 Cynthia Chou, Indonesian Sea Nomads: Money, Magic, and Fear of the Orang Suku Laut, RoutledgeCurzon--IIAS Asian Studies Series (London ; New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), 77.

- 15 Firdaus Sani and Pulau Sudong Descendant, Focus Group Discussion, Jul 19, 2024.

- 16 Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth,40.

- 17 Euan Graham, "Singapore at 50: Time's up on the 'fishing Village' Narrative," Lowy Institute, August 10, 2015, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/singapore-50-time-s-fishing-village-narrative.

- 18 Kelvin E. Y. Low, "Sensory and Embodied Narratives of Sea Lives and Displacement: The Orang Laut in Singapore," in Coastal Urbanities (Brill, 2022), 34, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004523340_003.

- 19 Pulau Brani Descendant, Focus Group Discussion, Jul 19, 2024.

- 20 According to email correspondence with the National Museum, Jul 20, 2024.

- 21 Pulau Sekijang Bendera and Pulau Brani Descendant, Focus Group Discussion, Jul 19, 2024.

- 22 Pulau Brani Descendant, Focus Group Discussion, Jul 19, 2024.

- 23 Michael D. Barr, "Singapore Comes to Terms with Its Malay Past: The Politics of Crafting a National History," Asian Studies Review 46, no. 2 (April 3, 2022): 351, https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2021.1972934.

- 24 Wee Ling Soh, "The Forgotten First People of Singapore," BBC, August 25, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20210824-the-forgotten-first-people-of-singapore; Jenni Marsh, "Forgotten Singapore: Evicted Islanders Grieve for Lost 'Paradise,'", South China Morning Post, May 23, 2015, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/article/1805255/forgotten-singapore-evicted-islanders-grieve-lost-paradise.

- 25 Clement Yong, "Pesta Raya: Remembering Singapore's Disappearing South Islander Cultures in Air Da Tohor," The Straits Times, April 17, 2023, https://www.straitstimes.com/life/arts/remembering-singapore-s-disappearing-south-islander-cultures-in-air-da-tohor.

- 26 Carmen Sin, "'Everything We Take Must Have a Purpose': Singapore's Urban and Island Foragers Find Food in the Wild," AsiaOne, April 5, 2024, sec. Singapore, https://www.asiaone.com/singapore/everything-we-take-must-have-purpose-singapores-urban-and-island-foragers-find-food-wild.

- 27 Vivienne Wee and Geoffrey Benjamin, "Pulau Seking: A Bygone Link to the Riau Sultanate," January 1, 2010; Brenda Man Qing Ong and Francesco Perono Cacciafoco, "Singapore's Forgotten Stories: The Orang Kallang Tribe of Kallang River," Humans 2, no. 3 (September 14, 2022): 138–47, https://doi.org/10.3390/humans203000; Timothy P. Barnard, "Celates, Rayat-Laut, Pirates: The Orang Laut and Their Decline in History," Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 80, no. 2 (293) (2007): 33–49.

- 28 According to email correspondence with the National Museum, Jul 20, 2024.

- 29 Peranakan Museum, "About The Peranakans," Peranakan Museum, accessed July 29, 2024, https://www.nhb.gov.sg/peranakanmuseum/learn/about-the-peranakans.

- 30 Hoe and Chong, "Nurturing the Cultural Desert," 6.

- 31 Barnard, "Celates, Rayat-Laut, Pirates," 33.

- 32 Sarafian Salleh, "The Orang Laut," Beyond Bicentennial - Perspectives on Malays, January 1, 2020, https://www.academia.edu/64462119/The_Orang_Laut.

- 33 Nabilah Husna Binte Abdul Rahman, "Tending to Wounds," Mekong Review, February 19, 2023, https://mekongreview.com/tending-to-wounds/.

- 34 Kwen Fee Lian and Narayanan Ganapathy, "The Politics of Racialization and Malay Identity," in Multiculturalism, Migration, and the Politics of Identity in Singapore, ed. Kwen Fee Lian, vol. 1, Asia in Transition (Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2016), 99–112, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-676-8_6; Kathiravelu Laavanya, "Rethinking Race : Beyond the CMIO Categorisations" (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2017), https://dr.ntu.edu.sg/handle/10356/152310.

- 35 Denise Ferreira Silva, "On Difference without Separability," in 32nd Bienal de São Paulo, 2016, https://issuu.com/bienal/docs/32bsp-catalogo-web-en.